It is Winter of 1972 and I am arguing with John McLaughlin which is rather unsettling as he is currently the post Jimi Hendrix Guitar God of the Universe. At the moment he is untouchable, not only for his musical fame and reputation, but also because he is a devotee of Maharaji Sri Chinmoy so anything he says apparently comes from a much higher place. It’s an excellent one –two punch.

His band, Mahavishnu Orchestra, is touring on the basis of their hit album, Inner Mounting Flame. He formed this group after graduating from the Miles Davis Jazz Rock finishing school where he played on some of the most famous albums of the era, albums like Bitches Brew and In a Silent Way. He also recorded several albums with Tony Williams and Lifetime as well as two solo records. The man has ridiculous jazz pedigree, is completely outfitted in white, and staring at my forehead while he speaks to me, apparently looking for that third eye.

My band, Merz Pictures, is opening for the Mahavishnu Orchestra in about 30 minutes. We are missing a few things; we have no hit record, no recording contract of any kind, nor any Miles Davis alumni pedigree. One of our keyboard players does think he is the second coming of Herbie Hancock but I know that doesn’t count.

We are also missing our sound check which is not our fault. Not one bit. The “Orchestra” was late and their sound check, while impressive as hell, ran way long. In that our Herbie Hancock guy plays acoustic piano we still have to muscle it on stage, mic it, and do some semblance of a mix. It is now clear that this is not at all possible when we see concert security letting people in.

If you are at a bar having a drink and you see the drummer casually setting up or some guy annoyingly repeat “Check one, check two” it’s no big deal. But this is not a bar, this is a big auditorium. This is a big deal. Doing a full sound check now would be like taking a morning shower and shaving in your cubicle at work, awkward and unprofessional to say the least. Something needs to be done.

I naturally try to take the easy way out so I ask one of the John McLaughlin’s roadies if we can use Jan Hammer’s electric Fender Rhodes piano which is still sitting on stage. On this Mahavishnu Orchestra tour, Jan is playing just piano and Hammond organ, although he is about to get heavily into synthesizers which were right around the corner. After Mahavishnu, he went on to do the soundtrack for Television’s Miami Vice. He also commented frequently that guitars would be made completely obsolete by the synthesizer as he felt he could duplicate any guitar tone. This apparently annoyed his recording cohort at the time, Jeff Beck, who was rather fond of the guitar but that is another story. On that stage that night there was not a mini moog or any synthesizer to be found. Just his Fender Rhodes which I am lobbying with the roadie to borrow.

“Hmmm, we’ve had some problems with his Fender, this is the second one we have had on the tour, you gotta ask John”

“He’s a jazz player, he won’t break it, he’s not Jerry Lee Lewis, plus this is because you guys ran long, it’s not our fault”

“Ask John.”

In 1972 there were two American jazz rock bands that were actually inventing new music. There was John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra and there was Weather Report. Very different music, but what linked them was jazz technique and compositional strength coupled with a desire to play harmonically sophisticated melodies and solos over kick-ass rhythms. Music that actually rocked harder than almost any rock music of the day, which, if I showed you a list of rock music from 1972, you would agree would not be too hard to do.

So I ask John.

I give him the narrative and as mentioned, he is staring right at my forehead. I have not set this up correctly because I approach him when I am on the main floor and he is on stage so he is looking down on me even though in real life he is about 5’6. To make it worse the angle of the overhead spots are on and they are creating this backlight effect which makes him hard to look at because, OK, dammit, I’ll say it, there’s this aura around his head. He gives me the same weak “we’ve had trouble with the Fender Rhodes” short story. I decide to go mid-west minimal on him and merely reply, “Yes, I understand that” and say no more. I just continue to look up at him expectantly and my divining spirit is whispering to me to that the first person to talk loses.

So, John McLaughlin is staring at my forehead and I am staring back at his aura, the audience is filtering in, and he finally says, “Compassion comes from within.”

I nod and walk away because I am definitely taking that as a yes.

I inform the roadie and we start balancing the P.A. We have a set to play and there is a lot to do. But I had learned something valuable; it is absolutely true that the first person to speak in a negotiation loses, and, oh yeah… something about compassion.

Our set began with an extended duet between our two keyboard players. Normally we are a trio but tonight we have a second keyboardist. Our guest Herbie Hancock keyboard guy is a technical marvel and he initially overpowers our regular keyboard guy with glistening arpeggio runs and waves of sound. The electric bassist and I are listening, still back stage waiting for our cue. We are listening very hard. It is interesting as we are in suspension, not on stage, not in the audience, but at the moment, professional listeners.

I know our regular guy, who is an excellent keyboard player is unhappy as it is obvious from the first bars that the guest Herbie Hancock guy is treating him almost as an accompanist so he can shine and dazzle. But then a curious thing happens; Herbie is playing so many notes and in fact is overplaying so much that he starts to drown himself out, it’s all sounding the same. Our regular guy plays a stout economical organ melody line that is simple but delightful and it cuts through like a knife. It is pure non-grandiose melody. That line develops, still unadorned and suddenly the whole balance shifts, Herbie is now comping, now backing him up and for the first time the music makes total sense. Just as I comment to the bassist that this sounds pretty good we realize together that they are playing our cue and we better get our ass on stage, not really sure how long that cue was being played. We hop to it.

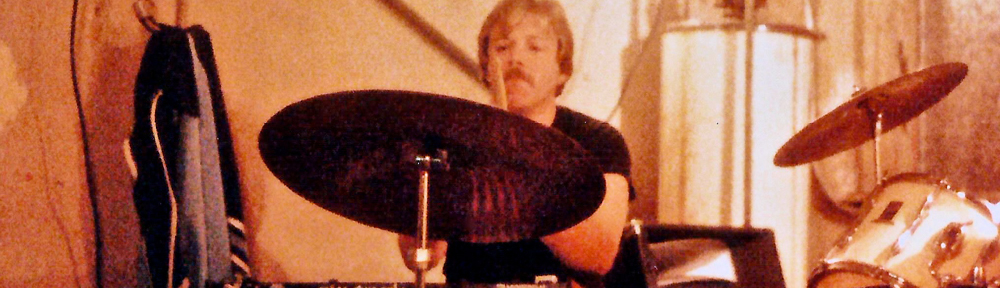

Playing drums is an interesting thing to do. It requires you to subdivide your brain and thought process into segments of automatic muscle memory and totally conscious creative thought. Other segments are counting measures and watching the invisible musical chart pass in front of you, moving from left to right to ensure you are playing the composition correctly, stops, starts, tempo changes, stuff like that. The weirdest thing is that you are moving all four limbs in syncopated or independent movement and you almost have to go reside at the top of your head and look down so you don’t screw it up. This is why drummers typically get very goofy facial expressions; the jaw goes slack, the brow furrows, whatever. It’s never pretty.

Creating these separate activities and having the brain monitor the four or five things going on also create a vacuum where you actually find your mind wandering because if you don’t kind of float, you run the risk of thinking too hard about a single function as opposed to being the capable multi-functional being that you need to be. And in drumming it can come tumbling down pretty quick.

So I am thinking. I am thinking the audience is receiving this unknown guitar-less instrumental music with keyboards and fuzz tones and odd time signatures fairly well. It is a known fact that people were smarter in 1972 than they are now but I am pleased. We are in our third tune and have yet to hear anyone impatient for Mahavishnu yell “You suck!” So apparently they were also more polite. As I drum through the composition I am also thinking about the long intro; how despite fantastic technique if you don’t have economy in your playing, if you can’t find traction in repeatable, hummable melodies, like any storytelling, if you don’t have a point, you are asking for trouble. You run the risk of drowning yourself out.

Exiting stage left in 1971-1972 was the legacy and memory of Hendrix and Cream, with combustion engine guitars and fluid drumming, entering stage right are the Allman Brothers, with their historic dual guitars and their fluid dual drummers, but front and center, kicking ass right now are the DNA offspring of Miles Davis.

Like any twisted double helix it gets complicated real quick. Now if I hadn’t gone with the double helix metaphor and “offspring” I would have used the word “incestuous” instead of “complicated,” but now that seems kind of creepy.

The mitosis begins with Miles Davis’ long time acoustic jazz quintet: Herbie Hancock who went on to form Headhunters, drummer Tony Williams, who founded Lifetime, and Wayne Shorter, the co-founder of the best and most enduring jazz rock band, Weather Report. Other Miles recording guest stars include John McLaughlin, who created Mahavishnu Orchestra with fellow alumni, Billy Cobham, as well as the other co-founder of Weather Report, Joe Zawinul. Joe appeared on several Miles’ albums, wrote and played on his seminal tune, In a Silent Way, which also starred John McLaughlin on guitar. Let’s not forget pianist Chick Corea who went on to form Return to Forever.

Miles Davis was the inverse of George Bush. He surrounded himself with geniuses, geniuses that made him the Zeus of Jazz. That is a tremendous talent, of course, but it is different than carrying the water yourself.

I think of the first Jazz Rock album, In a Silent Way. As mentioned, the title track is composed by Joe Zawinul, who also wrote Mercy, Mercy, Mercy and would go on to write Birdland. Joe wrote a beautiful melody played on guitar by John McLaughlin that would begin and close side two. But Side One is composed of a single track, SHHH / Peaceful. But here’s the whacked part: while nice and dreamy, lasting exactly17 minutes and 58 seconds at the 12 minute mark it pauses and the musicians start the piece over. At least that’s what I assumed until one day I really listened and I realized that Teo Maceo, Miles’ producer, had literally just started the tape over from the beginning. The band is not “taking it from the top”, they have all gone home. It’s just Teo hitting pause / rewind / play on the tape machine. Apparently he realized that album would be way too short without the redux or it was not structurally sound or something so he merely replays the last six minutes of the piece.

Now I am not a purist in anything that I can think of. But doesn’t that seem a little, oh, I don’t know, funky? And not in the Aretha sense of the word either. Can you name any other record that does that? Neither can I.

Miles has already been anointed so I need to be careful and keep my heresy on a leash here but his singular adulation is kind of working my last nerve. So let’s go back…

Be-bop, an energetic high speed form of jazz came about in the way late 1940’s because “cool hunter” superior musicians like Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie. Charlie Mingus and Miles got tired of being polite and allowing ex-Big Band guys back from the War to sit in. So they came up with tunes with odd, angular changes and ridiculously fast tempos. No one could sit in anymore because no one could play the music. All on purpose.

Everyone knows the Be-bop drill of course, incredible musicianship fueled by the relentless Charlie Parker, New York City and heroin until, of course, it wasn’t.

Then ‘Cool” took over, sometimes referred to as West Coast Cool. In fact, an excellent Miles Davis Ensemble with saxophonist Gerry Mulligan released Birth of the Cool in 1950. While that is a very good record, I always thought it had the absolute greatest title ever, Birth of the Cool. In homage to the title more than the music, a famous Los Angeles design show named Birth of the Cool thrives today, that’s how strong a name it is. But I was more than a little disappointed to learn that the name came not from Miles but from an obscure Columbia Record executive. Disappointed but not surprised.

A lot of recognition was given to Miles for going to modal music and getting everyone away from thinking about chord progressions. In jazz this is a big deal because the player’s basis is knowing “the changes” of a tune, namely the chord sequence so they can solo over it. In a run-on sentence this defines Be-bop, Hard Bop, Post Bop all the way to post-post Bop or Cool Jazz.

For some time Miles’ great quartet had embraced modal playing and composition, calling it “fast, no changes” or “freebop.” But the point is that Wayne Shorter, the main composer of that band, drove that idea. Yet everyone credits Miles alone with going modal. So we get all the way to In A Silent Way and it’s Miles headlining the session but it’s Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul and Teo Maceo carrying the water.

On Miles Davis’ next release, Bitches Brew, once again producer Teo Maceo invisibly takes center stage. On the first cut alone there are like a dozen edits, stops and starts, instruments drop in and out, electric piano chords hang and electronically loop in echo repeats. It makes Sgt Pepper look like a live recording.

So much so that Joe Zawinul who played on almost all of the sessions for Bitches Brew first heard the album in a record producer’s office a few months later and asked who that was. He simply didn’t recognize it. Teo, take another bow.

I’m not saying Miles wasn’t great and that Miles hadn’t seen it all and done it all. He had in the extreme. Sketches of Spain and Kind of Blue are jazz classics. He also had the internal fortitude to lock himself in his old bedroom at his father’s house in Alton, Illinois, and kick heroin unassisted and alone. Now that’s impressive. But I just wish he had shined the light a little more on those around him. After the mass migration of his semi-famous sidemen to form their own bands, to cash in on the underwhelming jazz equivalent of fame and fortune, Miles’ own output tanked. I challenge anyone to name a single interesting Miles recording after 1969’s Bitches Brew. Oh, if anyone mentions On the Corner I’ll actually make you listen to it.

So, five high powered bands, not even counting Miles’ band, unleashed at about the same time in a new invention: Jazz Rock. This was a form, now rightfully maligned, that for a very brief season created perfect music, created “new music.” Again, jazz execution played over rock rhythms to the exponent, rhythms that were unimaginable to either camp a season ago. Music where the actual composition is as important as the soloing, a welcome departure from the small ensemble jazz of the prior decades subsisting of theme / solo / solo / solo restatement of theme / end.

The initial recordings from these bands were uniformly excellent. Some still stand up very well today such as Chick Corea’s Return to Forever, Weather Report and Inner Mounting Flame. But something happened; the music fell apart almost overnight. Now referred to as “fusion,” the tempos increased and soloing became incessant, compositions were half baked and technique — loud blistering pointless technique– became the thing. It was soon evident that no one was home. And that is basically what happened to all these Jazz Rock super bands including Mahavishnu Orchestra. They all forget about economy, they forgot about melody. It was showy and stupid. Except for Weather Report.

Joe Zawinul had come from non-USA, non-black Euro worlds to end up playing with Miles and becoming somewhat famous for it, although he was accomplished before writing and recording for Miles. In fact, Joe Zawinul had played with Cannonball Adderley for years and had put out two solo albums. He was interested in electric instruments and had switched to electric piano (out of self defense from beat-to-shit acoustic pianos) before almost anyone. Joe was a player who could compose and a composer who could play.

So Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter left the Miles circle and formed Weather Report in 1971. Their first album is very good, not great. But in stark contrast to the devolution from all their brethren their second album, I Sing the Body Electric, is not good, it is freaking great. Some 35 years later it is still great and highly listenable. Both Joe and Wayne concentrated on writing serious melodic music, compositions sometimes arrived at by playing great music that they elevated and turned into finished works. No one could touch them. They were sincere and they continued to create “new music.” Drummers were Joe Zawinul’s nemesis but he loved bass players. Often describing himself as the “greatest bass player in the world,” he frequently doubled elegant, catchy bass lines on his synthesizers. Weather Report also introduced the real “greatest bass player in the world” to the world: Jaco Pastorius.

Ironically, they became the Miles Davis – Oprah Winfrey of the day. If you could get their endorsement to be on a Weather Report tour or recording and it was on. Joe actually brought in the rhythm section from Sly and the Family Stone for a short tour because he wanted more downbeat. Weather Report wanted to kick ass and kick ass they did.

The first time I saw Weather Report was about a year after the Mahavishnu Orchestra concert at Southern Illinois University. They were having a bad night — sound mix, something was not right. Not right to the point where Joe Zawinul temporarily walked off the stage mid-tune. He was extremely unhappy about something. But Wayne Shorter stood by the mic stand, eyes closed, listening to the prodigious rhythm section caravan along. Every once in a while Wayne would offer a line of melody followed by long spaces. Wayne was waiting until something compelled him to offer up another burst and then stand there, content and unhurried, listening with giant ears.

In fact Wayne Shorter is a human editing machine, the essence of economy. Cut One of Weather Report’s first album opens with a spacey over-amplified acoustic piano. The track, Milky Way, is a beautiful, pre-synth 1971 atmospheric piece in which Wayne’s entire contribution is a single, short note.

The second time I saw Weather Report was at a great jazz club in Chicago, the Quiet Knight, that summer. Admission was reasonable with the requisite two-drink minimum. If you were subtle, you could even stay for the early and the late set without paying a second cover charge. Based on the merriment between Zawinul and acoustic bassist, Miroslav Vitous during the break, I was guessing that they had already fulfilled the two-drink minimum from the bandstand and then some. But once the second set began their playing was impeccable. So much so that I felt compelled to go up to Joe Zawinul after the final number and thank him for the inspired playing.

When you approach someone as a fan you really have to have something to say which is harder than it sounds. Typically you are tempted to go with,” Hey, I really enjoyed your set” or something similar. The problem is that all the recipient of the compliment can do is shake your outstretched hand and say, “thanks for coming out” or some equivalent. No place to go, no information exchanged, no point.

All you want is a ten-second connection to show that you understood the compositions, convey your appreciation and confirm that if you could you would have given an ether facial to all the heathens who talked during the quiet interludes, but it just wasn’t possible. Maybe next time.

Modest goals. I approach Joe and with my girlfriend standing behind me. I thank him for a great set and go with the semi-lame musician question:

“Are you familiar with a British jazz rock band, Soft Machine?”

(They were the Frank Zappa of Europe, a slightly obscure but genius jazz rock band.)

“No”, says Joe shaking his head

“Well, um, I think maybe the keyboard player was influenced by you.”

Now this might or might not be true but it is complete bullshit because I don’t know that it is true and really, so what?

Joe raises his eyebrows in the Viennese version of “Ya think? I am only the single most influential jazz keyboardist on the planet.” Again, this is all spoken in eyebrow; the rest of his answer comes as a full body shrug.

My inanity completed, my girlfriend, Melissa Opela, offers her hand and says, “I really liked your playing.” She is knowledgeable about music and sincere. We turn to go and Joe says to Melissa, “Hey, where are you going?”

Melissa turns back around and indicates me, Mr. Inane, and says “I came with someone.” She gave Joe a very nice smile and we left. She dug it and I couldn’t blame her. Joe Zawinul was very high in our musical god hierarchy and she just got hit on by him.

I can’t swear he knew we were together but I was pretty sure. Melissa was nineteen and absolutely stunning, but still. On our way to the car I immediately began to wonder what would have happened if for some reason she had gone to see Weather Report by herself. Would she have awakened the next morning at the Chicago Hilton, reeking of Schnapps? But it’s better not to dwell on these kinds of things, that much I knew.

So, how could I forgive Joe for abandoning the stage at SIU, for mocking me with his eyebrows, for hitting on my girlfriend at the Quiet Knight in 1973, for dying way too early at the age of 75 last September?

Easy, compassion comes from within.

Or so I’ve heard.

John Trimble/2008