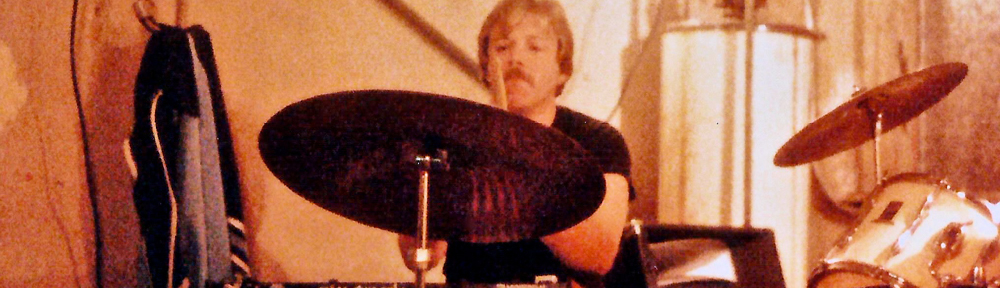

Even before seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan on February 8, 1964 (and the unlikely opportunity of seeing them live in 1965 at Comiskey Park in Chicago), I was fascinated by the drums. Watching heartbreakingly boring network variety shows, I would stare at the drum set, and it seemed like if you had all that equipment you should be able to do something musical without a lot of work. Once the Beatles washed over the joy-starved United States still stupefied by the hit on John F. Kennedy it was now an imperative: I had to have drums.

But beyond the drum set, the “group” was everything. One of the big Beatles takeaways was that being in a band was fun—the subtext was that someone always had your back. Humor could be perfected and enjoyed just for your own little band-village…all very desirable things.

Before having my own kit I remember seeing a kid from school, a little older than I was, who played drums in a Dixieland band. We’re on the city bus and all I can think of is that this guy has a drum set that he could be home playing right now so why the hell is he here?

Much to my siblings’ delight, I got a drum set ordered out of the Sears catalog, and made payments on time. Who wouldn’t love hearing someone teach themselves drumming on the third floor of your house? The set boasted the de rigueur early 60’s ugly red sparkle, and the cymbals were I am sure 100% tin. It was crap through and through, but I had a set and I could be in a band. And I am sure the bands were awesome: a never ending parade of fourteen-year-olds with drums and guitars, loudly and proudly demonstrating that we had no clue. None.

These bands all sucked out loud of course but this is what did not suck—starting in 1968 and living near Chicago, I got to see groups and musicians that would inform my musical thinking forever: Jimi Hendrix on his first two American tours with Soft Machine (more about them later) and a third Hendrix concert; Laura Nyro a year later; the first Led Zeppelin American tour with supporting act Jethro Tull at the small Electric Playground on Clark Street in Chicago (admission $5); the Allman Brothers with Duane Allman and Berry Oakley still alive; the Who with Keith Moon still alive; The Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Spirit, If, Country Joe…all great bands and we’re still talking about bands I saw in freaking high school.

The first listenable band I actually played in was Flag (1970). It had a lead female vocalist and featured an older, hot lead guitarist as well as an extremely gifted organist, Scott Mason. We did covers but they were interesting covers: obscure Yardbirds, Spooky Tooth, oddly a long section from West Side Story that always killed. The bassist was Randy Nutt.

If you are old enough to remember music from that time, circa 1970, most of the music was riff based. The guitar and bass would typically double and you were restricted from a rhythm point of view on every tune, even great tunes. These tunes are like the Jungian image of a snake eating itself. Hendrix would be the exception; Led Zeppelin and a hundred lesser bands would be the proof.

One day Randy Nutt started playing a simple bass pattern in rehearsal that was not a riff but a little melodic fragment that was both compelling and pushed the air ‘forward’ as opposed to putting you in a little box of repetition with nothing to do but play the line. I was entranced: it was just a little snippet, yet it was completely liberating. It was also the first time I had heard a bass line with someone I was playing with that wasn’t rock, wasn’t a riff, that was “other.”

By now we were starting to become really obsessed with Soft Machine (a seminal British jazz rock band that is the foremost example of Canterbury music, using fuzz organ for lead instead of guitar) but their music was so advanced, not presumptuous cheese-classical or “arty” like Emerson Lake and Palmer or Yes but just freaking hard. They played very unusual scales, did not have typical song construction, almost everything was in odd times. The drummer, Robert Wyatt, has the third most recognizable British voice on the planet. As an example, he kicks off their second album with a snappy tune called Pataphysical Introductions, singing the English alphabet backwards. The Softs were daunting and they were our heroes.

Equally important, but with more degrees of musical separation, was Terry Riley. This is a name you should know. Terry Riley (along with La Monte Young) is credited with creating the minimalism that enabled Steve Reich and Philip Glass. We didn’t even know the term minimalism at that time; we called Terry Riley’s music—particularly his album Rainbow in Curved Air— “cyclical.” And just like Soft Machine, it changed everything for us and for a lot of people. Here is why: each side of that record represents a musical vision and a path of how to approach layering keyboards or soprano saxophone; how to create little cyclical musical fragments that act as engines with lyrical gears engaging , melodic pistons firing and overlapping, creating micro rhythms that form, fade out and then form again. It is pure musical pleasure and nothing if not ‘new music’ which meant everything to us. Soft Machine bassist Hugh Hopper, referred to it as his “favorite dream record.”

Terry single-handedly parented a whole new school of keyboard playing (on a Yamaha electronic organ) where a short melodic phrase is introduced, glides along and then becomes a rhythmic unit as layer upon layer of new phrases are added. He also did this with his soprano sax playing on Poppy Nogood —Side Two of Rainbow in Curved Air — where using extensive echo and complex delays, he becomes over glacier-time a veritable big band of the future, where the music is changing, evolving but in slow motion. Terry also pioneered a lot of work in tape loops, again where repetition becomes a beautiful melodic device, with all of its subtle micro changes occurring constantly, delighting only the ear that is paying attention.

So when Randy played that one bass line, and interesting non-rock drum parts came to mind, I immediately thought—we can never be the Soft Machine or Terry Riley, but this is exactly what I want to play.

I wanted to accompany and build on fluid, elegant, unpredictable bass lines. I wanted to hear piano chords and great fuzz organ solos. And every once in a while, I wanted Randy to sing quirky lyrics about washing the car or the melancholia of a holiday. I wanted nothing more to do with guitar: in a sped-up world the guitar now seemed not to be ‘new music.’ I wanted the traditional lead singer gone; I wanted traditional lyrics gone; and I wanted to do original music because, if not original, what is exactly the point?

So Randy Nutt and I formed a band and immediately demanded that Scott Mason join. Adding Scott was critical; far and away the most technical, the most trained among us, he read music very well, and he got the concept, he understood the gift that was a fuzz box on a Hammond organ, and was able to solo like a banshee.

I wanted to call the Band “Hunchbacks and Dwarves” — a name that I actually still like a lot, although that was clearly the minority view. We were not the most handsome people in the Western World and I thought that the name could be a little warning flare off the bow, telegraphing that you will not be coming to see us for the charisma.

As a matter of fact, if you are walking even today near Northwestern University on Sherman Avenue near Noyes (it’s the third house from the corner, a large three-story white house), look down and you will see inscribed, enshrined perhaps in the pavement, “Hunchbacks and Dwarves.” If you look slightly south, you will also see written in the pavement, “Dog Movie.” That is the work of my sister Patti, commenting either on 1970’s Trimble family life or the world at large. Ignore that, it has nothing to do with the story. So, Hunchbacks and Dwarves was rejected and we became Merz Pictures instead.

“…Ooh the cyclicality…the clickity clack tonality…Merz is…”

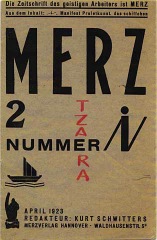

The name Merz Pictures comes from the German collage artist, Kurt Schwitters, who was taken with the fragment of the German word for commerce that found its way into one of his collages.

He liked it so much that from then on all his collages were presented and unified by the single name of “Merz” or “Merz Pictures.” The musical corollary for us was useful: we would do tunes and compositions, all different but unified by our playing and determination about what this music should sound like, so Merz Pictures—usually shortened to Merz—seemed to apply.Let me tell you about Merz:

There were many lineups of Merz, at one point it even featured drums / electric bass / electric bassoon and electric flute. The typical lineup was drums / bass / guitar or ideally keyboards. The keyboards were always the problem: as in finding and keeping the trained keyboardist who actually wanted to play our compositions; someone who would accommodate our pretty inflexible ideas on tone, repetition and structure. We were fascists about it which definitely made us less than cuddly over time. The first lineup (1971-1973) in many ways was the ideal as it was a trio with very occasional horns, again with organist Scott Mason. We recorded two powerful ten-minute compositions: Causcasian Love Song and Alternating Eyes. We did a reasonable amount of gigging considering that Scott was still in college. We opened for John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra. Things were progressing. Not in any financial sense, of course, not even close. Randy’s bass was starting to become a force (to this day he is still my favorite bassist) and he was developing total command of his fuzz soloing. Randy was actually asked to join the Paul Winter Consort, a pretty well-known ensemble who toured, had records out and an actual payroll. Impressively or foolishly Randy turned them down because he wanted to pursue Merz.

We thought of ourselves as cultural kamikaze—musical kamikaze pilots—as we knew the likelihood of making any money doing primarily instrumental music that was not rock and was not jazz was remote at best, especially in 1971 or 1972 when there was no new age anything.

At that time musical labels were even more binding (rock, blues or jazz) and no one knew how to label us. Not surprising as we didn’t know how to label ourselves. Cyclical rock? Fusion (soon and rapidly to self destruct on its own) was just starting, there were literally no places to play. Bar owners hated you on first listen… no 4/4 = no dancing = no sweating = no beer…We actually got surprisingly good reaction from audiences when we did secure a gig, despite playing completely original music, save for two Soft Machine covers which didn’t help, as no one had heard of them either. The music was loud but melodic, and if you weren’t paying close attention, it could pass for rock as there were drums, big Sunn amplifiers, electric basses and fuzz tones.

Then one day Scott wakes up and decides he would be a better acoustic bass player than keyboardist. The problem was that Merz already had an excellent bassist; we were screwed and it damn near killed me.

Now we had the real problem of finding a kickass keyboard player who liked our compositions, understood echo and patterns, and loved fuzz organ tone—which to us was religion and again not particularly negotiable. Someone who was a force. When Scott Mason was in the band we collectively bought a Hammond M3 organ, the little brother of the ubiquitous Hammond B3, but still this big-ass organ. Randy took a power saw to it, and a hundred electrical connectors, and we literally cut it in half so we could move it with just four (undoubtedly modified) volunteer roadies instead of six. So we did supply the organ and the fuzz boxes…“Hey, we are meeting you half way.” Or so we said.

But don’t forget, this is very early 70’s and there are absolutely no synthesizers available. There are Moogs, but they are at music colleges and studios and cost thousands and are still just glorified theramins with pitch bend. In a different section of this web site I recount our gig at Grinnell College where we opened for John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra who were on their first tour and about to be huge and single-handedly start “fusion.” Jan Hammer, their keyboardist and soon to be the poster child for synthesizers, also did the synth soundtrack for Miami Vice among other travesties. But then he still was playing a Hammond Organ and a Fender Rhodes electric piano, the only two mainstays of keyboardists at that time.

Organ tone was everything. It has to be either Fuzz (a note like a buzz saw, a glistening snake of a note) or creamy-washy chords, preferably with a wah wah pedal. It could not be that Booker T cheesy quintessential Hammond jazz tone: that was unacceptable. The problem was the majority of keyboardists were used to it and I guess they liked that tone. We were having none of it. Oh, and I might have neglected to mention that if you stomped on the fuzz box, you were very apt to feedback if you were not careful. And it was monophonic—you could not play chords, that would be just a wall of distortion. We didn’t care. Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine was the gold standard followed by other sympathetic organists (all English) who were all able to solo their asses off and they killed.

So…we really hated guitarists, except for Jimi, although we finally succumbed as their effects boxes got better over time. The effects boxes allowed guitarists to get a very thick keyboard-like note and get away from any ‘plucking” sound. But the problem was that most guitarists were totally predictable in their playing, with the usual set stock of note bends and tricks and runs, and it just wasn’t that musical. At least not yet.

Scott understood the ideal: a fuzz organ playing written thematic melodies over odd time signatures of bass and drums with the occasional whimsical vocal. The next formal lineup featured another phenomenal keyboard player: Fred Simon.

This second Merz took quite some time to assemble and was the quartet of me, Randy, Fred Simon on primarily electric piano and some organ, with Phil Gonzales on electric flute and effects. Both Fred and Phil were classically trained and absolute monsters. Fred today has countless CDs out; he’s a great, great player. The transaction was that they were both much more advanced players than Randy or me (particularly me) but we had the concept and vision. This might sound funny, but that was not a common thing to have. We knew what we wanted and exactly how we wanted to do it. So for about 18 months or so it was great. There are some live recordings that still exist, though the tape degradation makes it tough to listen to today. It was a hot band. The problem was that it was Merzian but not completely. It was sounding good but dangerously normal. Not all the time but still…

Fusion bands were now getting popular, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever and I felt we were getting infected. (Fusion was not good for you; it was all about thin writing, chops and fast tempos.) So we recorded, we gigged, entropy kicked in again and we moved on.

Here is how I felt the music should work…

To help imagine this, pretend to take a pleasing instrumental passage of any record you really like on an actual vinyl record. Take a pen and scratch the record so it skips for about a minute playing the same (hopefully interesting) part over and over until the needle skips again and stays in that ‘skip” for a minute before it moves again and so on for about 10 minutes.

Now go back and layer nice-sounding chords, different for each section; add a thematic melody. Go back again and create an interesting drum part that changes when the skip moves. Add fuzz organ soloing to some of the sections; add a vocal to one or two of the sections. Then learn the entire tune in toto—and that was the compositional ideal of what we were trying to do musically with Merz. It was both very fun and very hard to do.

Sometimes it sounded fabulous and sometimes, based on the smallest thing, the most innocent micro breakdown, it sounded like complete crap. We would on occasion actually induce skips on records and when they occurred—if they were really great—we would record them, loving the randomness and the musical accident-gift. We would then learn the skips and music, again not the easiest task but also very fun.

The reality…

The music was completely worked out, with almost no improvisation except for solos. This took forever to rehearse and learn. Just as one Merz lineup learned enough tunes by rote from me and Randy, we would get to a point where they would start to get tired of our fascist tendencies and would find a reason to quit the band. They did not exactly have to get creative to find reasons: very few gigs, almost zero money, actually it cost money, because we had to fund the rehearsal studio. I did not care that much about gigs, I was all about the recording of our tunes. But playing before an audience is pure harrowing fun and that would definitely have helped. Simply put we needed people who were technically proficient enough to solo well and play the parts, and if they were that good they would soon tire of gig lack, money lack and the (correct) growing perception that we liked their ideas only if they were in sync with our own.

So the band would spend months learning the tunes (Phoenecia Hotel, Creamora, My Little Margie, Caucasian Love Song, Paper Thin, Maria’s Cuba, Polar Queen, Slot Cars to Hell)…all tricky little bastards to learn—long themes, odd time signatures, cyclical melodies, a lot of starts and stops—and get proficient enough to put two sets together and then slowly entropy out.

I keep mentioning odd times: this refers to quirky 4/4 as well as actual odd meters like 10/4, 5/4, 6/8, etc. They was critical because the music could not have a steady rock backbeat because that was not …interesting. It had to overlap, turn corners, glide so that patterns and soloing would glide and turn corners and be compelling and be …new music. Jazz time was not acceptable either, no swing except in snatches played with ironic self awareness. As mentioned, Soft Machine (with Terry Riley as their inspiration) was the guide for all of this, and since no one else on the planet was doing it, we were determined to do it too.

It got so desperate that we literally drafted a pretty talented guy, Chris Bradford, a great friend of the band, to play keyboards even though he had no training whatsoever. This is called the Captain Beefheart Trout Mask Replica approach, where you teach every tune completely by rote and are selective about what you ask them to play. But he completely understood the tonal palette we were searching for. It was not completely successful, but Chris energized the band, he was funny, loved the music and was so knowledgeable about all our Merzian inspirations that it was worth the understandable lapses. He was our version of the Grateful Dead’s Pig Pen. Chris was ultimately more comfortable in Merz Pics, a more recreational recording spin off of Merz featuring keyboards and guitars with Randy, Kurt Jung, and Jeff Levine, where among other things he co-wrote and played organ on a wonderful dream state keyboard and vocal tune epic, Neon Decade.

Like Rayon it’s C’mon, C’mon” (1977–1983)

So Merz is now a quintet with the addition of electric cello played by seasoned player Janet Haarvig, Kurt Jung’s effect- laden electric guitar, and the aforementioned Chris Bradford on organ. This lineup did some good recordings, we got a smidge of airplay and had a handful of gigs, but it was not the ideal by any stretch.

The band stripped down to a trio once again with just guitar, and the band became more aggressive because with only three parts there was no place to hide while having to sacrifice some complexity of the arrangements. I began to do much more writing (It’s a Clambake, Too Many M’s in Mormon) where before Randy did the majority of the tunes. Had some gigs, our new portability did not hurt. A friend of the band, Glen Zazove, arranged for a pretty high quality video of Merz performing our tune Now You Know at Northwestern University.

But there was a sense that we had done our canon enough. We were not through playing together; there was no need to disband anything, as Randy and I continued to play together. More importantly, Merz had become as much a sensibility as a band or composers’ workshop, and that sensibility was not going anywhere; it was now baked in.

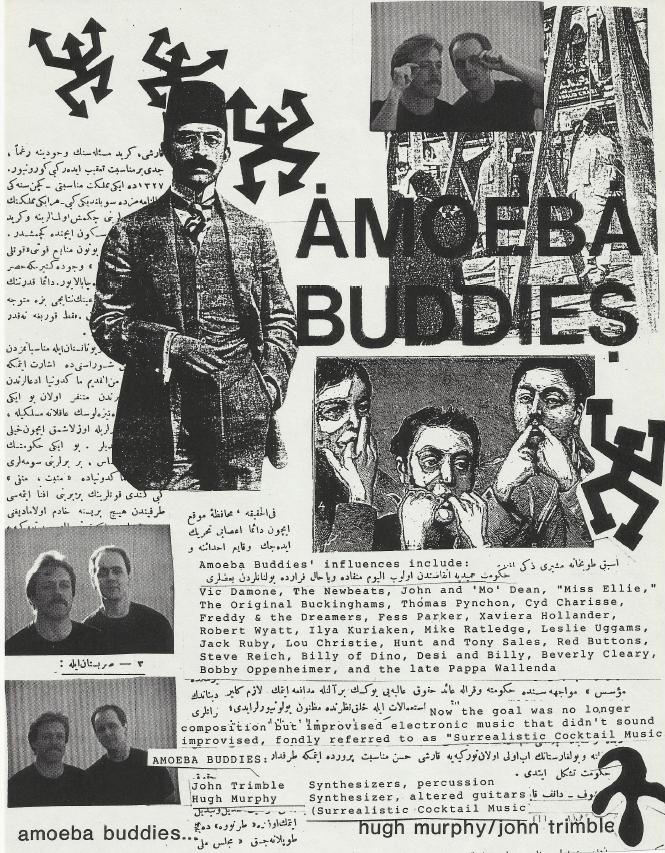

One frustration was that Randy and I found a like-minded musician, Hugh Murphy, too late for him to be part of Merz. He was a guitarist but had great technique—a fine soloist with total command of his effects boxes. He was a force. He was also someone that you could be with for long stretches without thinking of strangulation, not always true of other musicians.

In my own goofy way, I was by now playing a lot of keyboards with Randy on bass, so Hugh was a great fit either with me on drums or on keyboards. We added a very strong drummer on occasion, Mark Litton, and called it Queer Career. The name comes from my idea that pursuing music or any arts in this country is, in fact, a queer career. Here is the party line on Queer Career that appeared on our home studio CD releases:

“Queer Career is an improvisational ensemble. Using guitar, bass, drums and keyboards and real time loops they created modern cyclical music. All performances were recorded live with no overdubs.”

Randy, Hugh and I continued recording and playing. It was great and bittersweet as Randy and I were struck by how much easier it would have been if our paths had crossed a decade earlier. Hugh was that good.

It was also soon an end of an era as Randy moved to Miami in 1986 so that his wife Carol could accept a teaching position at the University of Miami. Her field of study is ants. We closed down the studio on North Clark Street in Chicago after ten years and suggested to the landlord that they do a thorough cleaning.

Hugh Murphy and I formed a duo with me on cyclical looping keyboards and Hugh on keyboards, guitar and effects. Great fun. We were commissioned to do the soundtrack for a local Chicago presentation of Waiting for Godot and had occasional gigs. We marketed it as “Surrealistic Cocktail Music.”

This was the first solo initiative. Using on board keyboard multi-track layering and drum machines, I was able to create really dense cyclical music. Although harmonically limited, I was able to be my own fascist leader of one, and was free to attempt my concept of cyclical music without having to do any negotiations with the other real musicians. Quite necessarily I was also able to re-record keyboard patterns before doing all the recording in real time due to my limited technical proficiency and modest recording arsenal. I can still listen to a lot of this, particularly These Zebras Have Stripes!

I pursued this approach for years and it was great fun. Then starting in 1995, with more resources, I was able to manifest Demand Badger Octet.