When attempting to assess the individual and collective effort that was Matching Mole, you realize what a long shadow Soft Machine cast upon them. The natural first question to ask is ”how important were they?” quickly followed by “compared to what?” Compared to Soft Machine at their prime? Compared to their peer Soft Machine of 1972? Compared to other progressive music of their day: Coliseum, IF, King Crimson, or other Canterbury bands?

In 1972 Soft Machine isn’t really Soft Machine anymore; their slide has begun. Caravan exists, Pink Floyd exists, as does Egg. Henry Cow has just begun, with Hatfield yet to come. So for context it is important to acknowledge Matching Mole as an artistically fearless ensemble intent on creating new music that also bridged the first wave of Canterbury bands into the second.

Matching Mole continued a sound and approach that was fairly unique to Robert Wyatt and his earlier efforts in Soft Machine. They were an accomplished group of musicians playing primarily instrumental “new music” without any clear antecedent that also featured vocals. Soft Machine did not echo anyone nor did Matching Mole.

There were other jazz rock ensembles with singers, certainly, but two things made both of Wyatt’s bands different. First: the abandonment of normal song structure of intro / verse / chorus / solo / verse / chorus. Other bands such as Pink Floyd, Chicago, IF, Coliseum — even Caravan — all used fairly conventional song structure, admittedly with long sections for blowing. Hand in hand with this was the second characteristic: Robert’s use of voice as an instrument, with no lyrical content interspersed with sections of lyrics dealing with actual real life. In contrast to their peers and the fusion ballast that was to come, Matching Mole furthered the form that was to be a definition-point of Canterbury music.

As unrelated as it might seem, the closest thing historically, outside of Soft Machine, to that same musical perspective and spirit was John Coltrane and band chanting “A Love Supreme” over and over before returning to their shattering instrumental playing on their breakthrough recording of the same name.

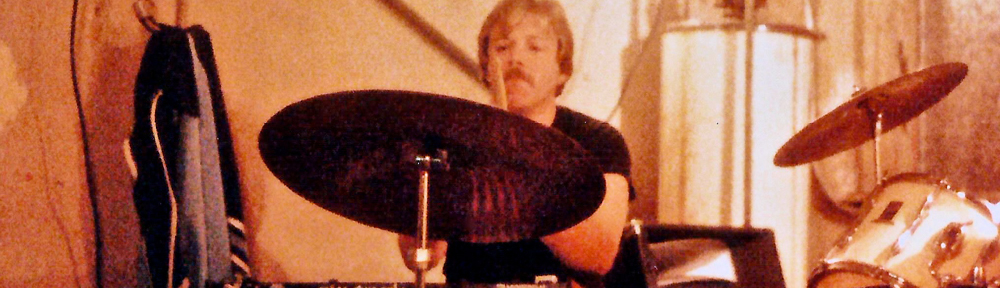

On Robert’s drumming in Matching Mole

There is no easy way to say this. Robert’s drumming in Matching Mole is a subtle downward arc through the two studio albums and the live releases. His drumming on the debut album shows typical Wyatt urgency, but by March he sounds fed up and uninvolved.

Robert’s playing on Matching Mole alone elevates this recording, despite the album’s fairly short length. The well-known issues of the under-funded and technically plagued recording sessions still don’t subvert his playing and the music as a whole. His goal of playing electric improvisational music in 4/4 time is realized. The most successful track on the debut, ‘Part of the Dance,’ delivers sonically as well as individually with fluid sections of improvisation. It is quirky and unique, ending with their instrument of the moment, the mellotron.

‘Beer As in Braindeer’ continues his drumming experimentation with the Echoplex from The End of an Ear. It’s rhythmically limiting but also new ground as no one else was using it on recordings. The drumming on ‘Instant Kitten,’ while short, also features the best aspects of Robert’s distinctive playing.

Wyatt’s playing on Little Red Record is still engaging and urgent but again, slightly less so. Despite inspired moments there is a falling off, as the drum parts seem somewhat casually arrived at. His drumming on the album still works, but primarily because most of those compositions work so well overall; the drum tracks by themselves are not Robert at his most compelling. Robert is such an interesting drummer that even his marginal parts still sing, yet the difference is discernible. There is a noticeable lack of joy in his drumming. Compare anything post-Mole debut with his playing on Keith Tippet’s Dedicated to You, But you Weren’t Listening, as an example, and the contrast is vivid.

Where Robert did shine on Little Red Record is MacCormick’s ‘Flora Fidget,’ with crisp playing on an up-tempo composition with interesting changes, and a thematic cymbal solo on a trio recording of drums, piano and bass.

‘Smoke Signals,’ a clean, angular McCrae composition, is the album’s most memorable track despite its rather odd structure: a statement of theme quickly moving into an enveloping electronic piano fog that seemingly ends the piece. Then, from stasis, the theme reemerges. It is haunting and atmospheric and stands up beautifully even today. Robert’s playing sounds like no other. He has the ability to drum energetically, almost soloing, and yet purposefully not moving forward.

This is the same approach used so effectively at the very end of ‘Moon in June’ under the sung snippet of the Kevin Ayers lyric. Drummers play “time” and time moves forward. To create a drum / rhythmic atmosphere that remains musically stationary is uniquely Robert.

Wyatt’s drum tone on Matching Mole / Little Red Record

On the Matching Mole debut, Robert has excellent drum set tone still similar to his Third / Fourth Soft Machine recordings although, again, not nearly as well recorded. Tight, crisp snare, full resonating tom-toms, and a heavier use of cymbals and cymbal washes. Even in this somewhat murky recording Robert rises above it in cliché-free drumming. His snare drum tone alone is worth the price of admission.

Conversely, on every single track of Little Red Record, Wyatt uses his snare drum with the snares flipped off; normal snare tone is not used once, unheard of for that time. Although he is using his standard late Soft Machine set-up on his Ludwig kit — bass drum, rack tom-tom, single 18” floor tom-tom and snare — he is obviously looking for a non-jazz, non-rock tonality.

For live performances, at least, he made three adjustments. First, he took a smaller crash cymbal and placed it under his larger ride cymbal in a rather unconventional placing: both on the right hand side of his bass drum. Second, he returned to using his 16” crash cymbal above the hi-hat. This allowed him more varied cymbal tones, which are evident on the live recordings in particular. The third change was sonically disappointing. At some point during or after making Little Red Record, Robert removed the bottom head from his rack-mounted tom-tom, which negated the inherent resonance of the drum. This was very in vogue in the early 1970’s with a lot of rock drummers doing the same (John Densmore of the Doors, as an example). But sadly it just kills the tone of the drum.

Unfortunately, recording engineers often promoted it as it made the drum sound dead, with no ring or bounce, and therefore easier to record. This also enabled Robert to use the tom-tom more as a snare drum, particularly on ‘Nan’s True Hole,’ again getting away from the Buddy Rich school of drumming, but it was tonally expensive. The additional problem is that either producer Fripp or Robert Wyatt drastically altered his sound by employing conventional studio muffling and dampening to both his tom-toms — with spectacularly bad results. It robbed Wyatt of his sound identity; the drums sound constrained, commercial and ordinary, particularly on ‘Nan’s True Hole.’ Even with substandard recording quality, the live Smoke Signals and March both feature better drum tone than Little Red Record.

There is nice cymbal work on ‘Brandy as in Benj,’ one of the best tunes on the album. But the cymbals were recorded so much better and are so much more pleasing than the drum tone that it is startling when the drums reappear after the thematic cymbal solo.

Matching Mole and Little Red Record

This debut featuring ‘O Caroline’ is what record executives were probably hoping he would have delivered as his solo outing, rather than the completely unmarketable and almost unlistenable The End of an Ear.

It was, however, immediately evident that Dave Sinclair was not the keyboard answer for Matching Mole. He possessed good tone on his Hammond and was capable of creating interesting extended fuzz solos. What was lacking was his ability to organically “comp” behind other soloists to create a textured background to hold the music together as it changed, stopped and started within the actual pieces. More importantly, a musical “universe” and point of view did not emanate and unfold from his keyboards the way it did with both McCrae and Ratledge.

Interestingly, the playing and group dynamic are actually better for Wyatt, MacCormick and Miller on the first record, while the actual compositions are far stronger on Little Red Record. Those tunes, most by McCrae, are much more vibrant and realized than anything on the first outing. Other than ‘O Caroline’ there are essentially no memorable melodies on Matching Mole. It is rich with atmosphere and mood but contains no lasting melodic imprint.

While Little Red Record is very strong compositionally, the overall recording quality is suspect. It is tonally a much “brighter” album but it lacks depth. Certain passages seem almost over-produced and other tracks sound as if they were done with minimal rehearsal at best. The fact that the record maintains as well as it does after all this time is in spite of producer Robert Fripp, who did not do anyone any favors here.

Other than a nice solo on ‘Righteous Rumba,’ Phil Miller was essentially a non-entity on the recording. Dave McCrae carried the record with both his playing and his tunes. Despite its limitations, the debut album featured a quartet with nice organic interplay; Little Red Record offered a strong trio with very occasional guitar. Despite the presence of an eventual guitar genius in Phil Miller, Dave is the only compelling soloist on Little Red Record and the instrumental star of Matching Mole.

But make no mistake despite its flaws, Little Red Recordstands up remarkably well some thirty-plus years later. In many ways it should be considered a great record.

Two musical problems: tone and execution (plus concept!)

Tone

Dave MacCrae is a very accomplished electric pianist. In the early 1970’s that was no mean feat. At that time the Fender Rhodes was the only acceptable option and was ubiquitous; everyone in jazz was using it. The Fender Rhodes had a built-in deficiency: at louder volumes it would inherently distort, particularly the lower registers. This was separate and apart from any distortion caused by amplification.

In 1972 there were exactly two Fender Rhodes pianists worth noting: Joe Zawinul of Weather Report and Dave McCrae. Both were very technically proficient, compositionally minded, and intent on creating new sounds with the Rhodes. Both had to integrate the inherent distortions of the Rhodes into their music and find ways to expand the sonic palette of the instrument. Both came up with the same solution: the Ring Modulator, often combined with an Echoplex. This Ring Modulator allowed sustained notes to achieve decidedly non-piano synthesizer tonalities, evident both on Zawinul’s I Sing the Body Electric and all of MacCrae’s Matching Mole recordings. The problem is that the tone is essentially unpleasant. It is grating, dark, unwieldy and it actually hurts, much more than fuzz organ or bass.

While Zawinul eventually solved his problem by moving almost exclusively to fledgling synthesizers for non-piano tone, that option was not available to McCrae. His only other voices were the occasional organ and acoustic piano lines heard on Little Red Record, which sound marvelous and clean, undoubtedly due to contrast. Good examples are the organ backing on ‘Righteous Rhumba’ or the cyclical acoustic piano part behind the vocals on ‘Starting in the Middle of the Day.’ It works completely and captures a lovely pre-Steve Reich minimalist repeating pattern.

Execution

Simply put, Bill MacCormick is an interesting bass player who moves comfortably with Robert through the shifting Mole rhythms. The problem is that he is not a particularly accomplished fuzz bass soloist. His 6/8 fuzz solo in ‘Marchides,’ as an example, is eager and energetic, but he hits an unacceptable number of bad notes. Actual mistakes, poor intonation, for measures at a time in a studio recording. I find it incredible that they did not re-record his solo on ‘Marchides.’ Musical notes are either in key, right or wrong, unless occasionally used for effect. That is the tyranny of music. The thought that they listened to that solo in the control booth and said “OK!” is hard to understand. By the recording of the live Smoke Signals the 6/8 solo space in ‘Marchides’ had been shortened and assigned to Phil Miller.

Concept

One should not require coherence from surrealism. But the lack of cohesion on ‘Gloria Gloom’ between the audio prelude of three non-connected narratives without any payoff reduces the effectiveness of some following great lyrics that question “contributing to the already rich.” A similar problem exists with ‘Nan’s True Hole.’

If a dreamlike musical atmosphere is the goal, that is fine, but more effect and illumination might have been realized by connecting the layered spoken word with the sung lyric.

It’s the Mole!

The works of Matching Mole are almost more easily heard and appreciated in 2006 than they were in 1972. In 1972 the understandable, incessant, undoubtedly demeaning comparisons to Soft Machine were difficult to ignore and to filter out. Now out of the shadow, Matching Mole’s music still breathes surprisingly well. Perhaps other than the first two tracks of Fifth, the Matching Mole studio work endures better than any post-Wyatt Soft Machine recordings.

Sometimes distance tells us lies and sometimes it tells the truth. Far from myopic, Matching Mole produced wonderful music.

John Trimble / Indianapolis 2006

So, I found an easy and enjoyable way to access a lot of this stuff, some of which I missed the first time around by creating a “Soft Machine” station on Pandora and then tweaking a little. Matching Mole, Egg, Hatfield, Caravan, etc. Well written band bios too. Enjoying this music once again….Probably more than ever…..